What can we be doing today that fireproofs liberal principles?

The Four Corners of Liberalism: A Conversation with Emily Chamlee-Wright

The Great Forgetting

This summer, a 1946 civics textbook sat alone on a side table in a vintage home store in Iowa. I wasn't even sure it was for sale. I'm the kind of person who calls old books 'friends,' and this one demanded immediate attention. I sat down and started reading right there—my family just sighed and went on shopping, knowing they'd lost me.

Pioneering in Democracy warns that democracy isn't self-sustaining. The timing of its publication is important: January 1946—just months after World War II ended—when the fragility of democracy was still raw in everyone's minds. The book’s foxed pages carry a warning from the editor: Democracy involves "understanding and managing human relationships" and must be learned through "active participation." The preface cautions that children watching adults constantly argue about democracy might conclude the system itself is broken instead of understanding it is an ongoing, living process of negotiation and compromise.

In 1946, the authors of Pioneering in Democracy saw clearly that democracy could be lost if not actively taught and practiced. Now, almost 80 years later, we seem to be grappling with this loss.

Emily Chamlee-Wright has a name for this phenomenon: the great forgetting.

"We've become so accustomed to the freedoms that we enjoy," Emily tells me from her office at the Institute for Humane Studies (IHS). "We cooperate rather than prey upon one another, not because there's a police officer watching us, but because we've internalized those norms. That auto-response is part of what makes society work." Her voice carries both wonder and worry. "The problem is when our defaults are always on autopilot... we can forget where all the benefits and bounty of our current circumstance comes from."

As President and CEO of IHS, Emily works to counter this forgetting. IHS has built a community of over 7,000 scholars and policy experts who ensure classical liberal principles aren't just preserved as an intellectual tradition, but actively put to work in the world—exactly what that 1946 textbook called for.

Discovering the Four Corners

Eight and a half years into leading IHS, Emily still sounds delighted by her job. "It's like I get to be the provost of the best university in the world," she tells me, "but it's just a distributed university, and I only have to work with the scholars who want to work with us."

This joy makes sense when you understand Emily's path to these insights. She chose to attend George Mason University not for its economics program, but because it was close to her dance community in Washington, D.C., "I totally fell into a community that was committed to classical liberal principles," she laughs. A dancer stumbling into economic philosophy—it sounds like the setup to a joke only a policy wonk would appreciate.

"As someone who was a somewhat accomplished amateur in the arts, I had tremendous freedom," she explains. "The freedom to innovate and the freedom to participate in expressive behavior, I understood viscerally as an outcome of living within a liberal, democratic society."

This explains so much about Emily's approach. How many economists understand freedom first through their bodies, movement, and expression before they ever crack open Adam Smith?

As a young economist, Emily asked big questions: "What would the world look like if all women on the planet had economic freedom? What value would that open up not only for those women but also for their families?" She understood that women globally were "disproportionately responsible for providing care, education, nutrition, and health to the next generation." Economic freedom for women meant human flourishing for everyone.

"I've always been a kind of crunchy granola version of the classical liberal," Emily says. Not the "purely analytical, cut and dry" type. She's interested in the messier, more human bits.

From these experiences emerged what she calls the Four Corners Framework. "My way in was economic freedom," she explains. "And the close cousin there is political freedom." But there were pieces missing. "The lessons from Tocqueville, for example, are really, really important. Political culture matters as much as the formal rules of the game. It's also the informal norms that matter."

For Emily, economics isn't just transactional relationships—"it's a sphere in which we make real friendships where trust matters." She came to understand that civil society and intellectual openness are essential complements to the political and economic elements of liberal democracy.

"Political freedom, economic freedom, civic freedom, and intellectual freedom," she lists the four corners of liberalism. "None of them is a sufficient condition for the system as a whole. Each needs the others. Each pulls and tugs against the others."

What I love about Emily's approach is how she embraces this tension as essential. I believe the ability to hold a paradox—to resist collapsing complexity into false binaries—might be the most important skill for our times. Emily agrees: "It's not a bug in the system, it's a feature that they tug and pull against each other in ways that are in tension, but it's a productive tension."

Learning to Be Lovely

In talking with Emily, I bring up my conversation with Lenore Skenazy about trust and childhood autonomy. When we don't let kids practice decision-making, I wonder, how do they develop real virtue?

"Adam Smith had a lot to say about that," Emily says, then laughs. "That's the running joke in our family. Whenever somebody says something insightful, I'll say, 'Well, you know who had a lot to say about that?' And my kids go"—she adopts a long-suffering teenage voice—"'Adam Smith.'"

Emily tells me about a moment when her daughter, now grown, was young and failed to stand up for a friend being picked on. "She was totally beating herself up over not being a better person to a friend," Emily recalls. "And I kind of let her sit and stew in that."

Now this is my kind of parenting advice.

"I didn't want to make it okay for her immediately," Emily continues. "That was the training ground that was helping her to internalize what virtue looked like." Years later, her adult daughter told her: "I was so mad at you. I really wanted to be let off the moral hook, but thank you for not doing that because... I don't want to be that person as an adult."

This is what Emily, channeling Adam Smith, calls developing our "impartial spectator"—that voice in our head that judges our behavior from a distance. It's the difference between learning to avoid blame and learning to avoid being worthy of blame. The difference between being loved by others and “being lovely,” by which Smith meant, being worthy of that love.

I think about my conversation with Lenore Skenazy, how too often we don't let kids walk home alone anymore. Emily builds on this—we don't let them sit with moral discomfort either. We rush to reassure, to excuse, to make it all okay. And, in doing so, we rob them of the chance to develop that internal compass and to prepare them, as our founders would have considered, for public life.

But this isn't just about parenting. It's about all of us in this great American experiment, and what Emily calls the "sacred obligation" that holds liberal democracy together—journalists committed to truth, judges feeling transformed by their robes, civil servants serving something beyond themselves. However, these obligations can't be written into law.

"If we lose that," she says, "that’s the toothpaste that's going to be really hard to shove back into the tube."

The Rage Industrial Complex

So how did we get here? I ask about root causes, and Emily describes what she calls a "rage industrial complex." Each side creates a "permission structure"—her term—that says the stakes are too high to follow normal rules, to maintain civil discourse, to uphold democratic norms.

"I get the question, 'Well, who started it?'" she says. "It doesn't matter."

"This all sounds very much like parenting," I tell her, and we both laugh. But it's not funny, really. Especially right now. We're a democracy acting like children who have yet to develop a moral compass, each justifying increasingly terrible–even violent—behavior in response to the other side.

At IHS, Emily has taken a practical approach in response: they've banned war metaphors entirely. "We don't talk about freedom fighters for liberty. We don't talk about soldiers or winning battles," she explains. "What a terrible metaphor. If you're in the ideas world, it's not a battle."

She's describing what the author and columnist, Amanda Ripley calls the difference between "high conflict"—the kind that distills into good-versus-evil feuds—and "good conflict," where people can disagree productively while maintaining curiosity about the other side. When we use combat language, Emily argues, "we're going to be doing what people in combat do, which is to arm up, identify the enemy, dehumanize." Her observation hits especially close to home right now.

Ripley calls them "conflict entrepreneurs"—those who profit from keeping us trapped in high conflict where the fight itself becomes the point. And heartbreakingly, we continue to see what happens when high-conflict rhetoric spills over into violence.

Piercing the Collective Illusion

What buoys me most about our conversation is Emily's optimism. Her passion and commitment are infectious. She's not blindly hopeful—she calls it "warranted optimism"—but rather is genuinely convinced that change is possible because in one-on-one conversations she finds "an amazing degree of radical agreement around basic liberal principles."

The problem? We're trapped in what she calls a collective illusion. She tells me about Todd Rose's book, which tells a story about a town dominated by one woman, "Mrs. Salt," whose views everyone pretended to share out of fear. Everyone thought her views represented the community, but almost no one actually agreed with her.

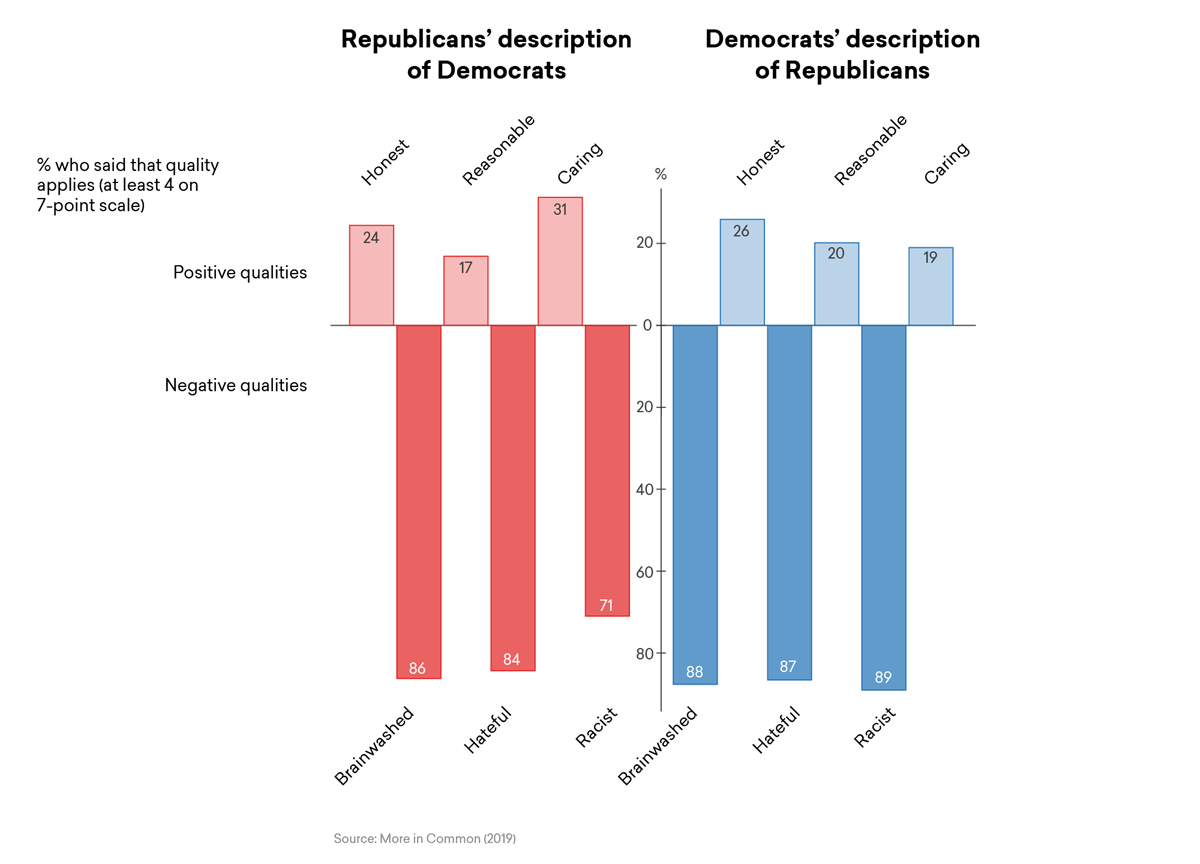

The Mrs. Salt dynamic predates social media, but today's version is measurable. Research from More in Common documents a "perception gap"—Americans overestimate how extreme the other side is by nearly double. Democrats think Republicans are far more conservative than they actually are, and vice versa. We've misread the room entirely.

Modern platforms make it worse. Emily points to research showing that on some platforms the loudest 10 percent dominate the conversation. The loudest fraction becomes "the public." As Henry Farrell argues, these are malformed publics; together with Hahrie Han, he further shows how AI and various platforms can disorganize democratic publics.

So what do we do? "Pierce the bubble," Emily says. Name the illusion. Stand up and say, "I know this might not be popular, but I believe in basic liberal democratic principles." She'll get hate from both sides—"'Oh, liberal values are so 10th grade civics class' to 'If you’re merely liberal, you're morally bankrupt.'" But she does it anyway.

What Comes Next

Finally, I ask Emily what she's monitoring.

"Right now, there's a lot of commentary around our political moment," she says. "The thing that I've got my eye on is what comes next."

She sees two possible futures. In one, we experience illiberalism, watch the breakdown of liberal norms and institutions, learn from it, and "usher liberalism back in full force." But she's not confident that's the lesson we'll learn.

"I don't know that the feedback loop is as robust as it needs to be. What I fear is that we get illiberalism by another flavor with just different people in charge, and it could get worse, not better."

"What can we be doing today that fireproofs liberal principles?" she asks, and I know it is not a rhetorical question.

Now, writing this piece, I return to that 1946 textbook on my shelf. Its author, Edna Morgan, believed democracy must be lived, not just taught. That pioneering democracy requires sustained practice and experience. Emily shares this conviction, but with greater urgency—we need to remember what we've forgotten before it's too late.